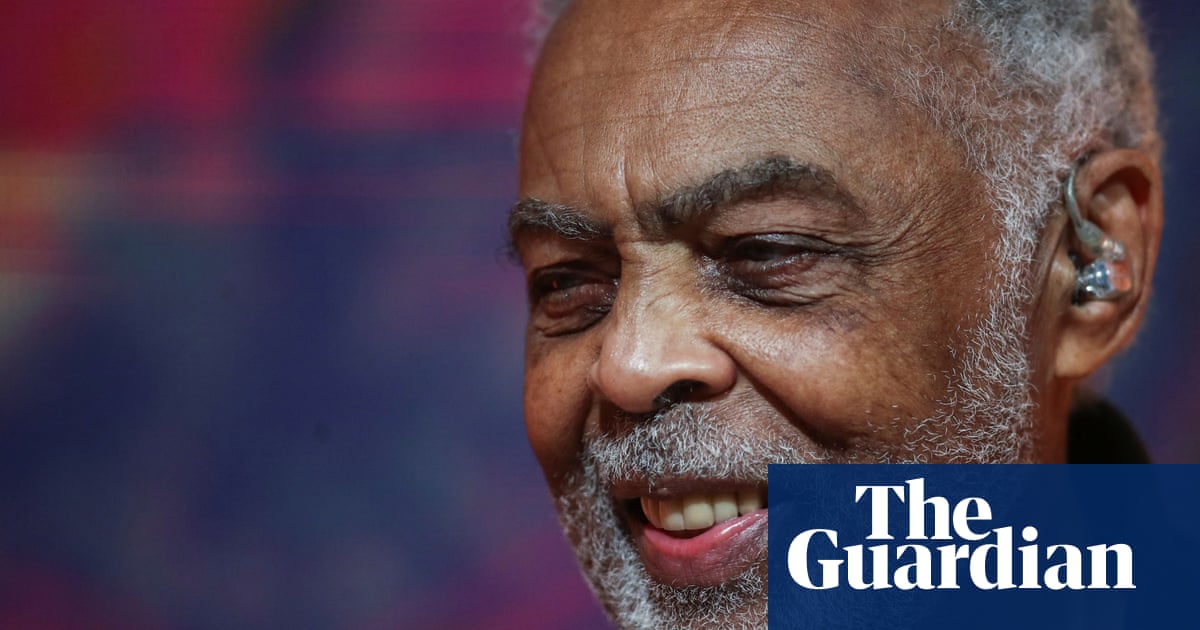

Gilberto Gil at 80: ‘Bolsonaro has a retrograde worldview, an opposition to any advance’

The Brazilian music legend Gilberto Gil has recorded more than 50 albums, spanning samba, rock, funk, bossa nova, reggae, forró and disco, plus the liberated sound of tropicália, the movement he helped to create in the 60s. There may be musicians who can boast similar persity and success – but there are none who have performed at the United Nations with the secretary general joining in on percussion.

At the end of the 1980s, Gil, who was born in 1942, let his political as well as his musical side flourish and became a city councillor in Salvador. He reached higher office in 2003, when a dreadlocked Gil accepted the role of minister of culture for the then-president, Luíz Inácio “Lula” da Silva. That year, he performed his 1979 hit Toda Menina Baiana (Every Girl from Bahia) on the UN stage in New York, accompanied by Kofi Annan. He remained in the position until 2008, a term the writer and composer Luiz Antônio Simas says is “remarkable, because it showed that culture takes place in an everyday dimension: on the corner, in the bar, at the square. It was a policy so advanced it should have become a model.”

Instead, the ministry of culture was disbanded in 2019 at the beginning of the far-right government of Jair Bolsonaro, which cut funds and started to demonise the sector. On a video call from Perugia, Italy, during a European tour celebrating his 80th birthday, Gil does not hide his displeasure.

“The regression to which we were subjected is impressive. But what to expect from a person who prefers to open a shooting club to a library?” he says. “It is a retrograde, reactionary worldview, which demonstrates an opposition to any type of advance, which does not want to live in the agility of the future and the permanent challenges that this implies.”

One of the founders of the ecological NGO Onda Azul in 1991, Gil used to say that he has been working for the environment since he understood himself to be a citizen. But in recent times, this work has increased – he calls the deforestation of the Amazon, abetted by Bolsonaro, “a huge depreciation of Brazil’s image to the world. It’s as if we are decivilising ourselves.”

In 2017, Gil joined musicians including Elza Soares and Maria Bethânia to record the song Demarcação Já! in favour of the demarcation of Indigenous lands; in 2021, he participated in an online festival to raise funds for an NGO of Indigenous peoples and he recorded the song Refloresta in support of a campaign against deforestation. He says the murder of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips last month was “a barbaric crime”, describing the men, who were documenting incursions into Indigenous land, as “two important agents in the fight for the preservation of our natural wealth and the viability of a future of fairer and more balanced environmental relations. But a feeling of grief strengthens the fight.”

Gil, born in Salvador, Bahia, in the north-east of the country, rose to fame at 25 with the song Domingo no Parque. Influenced by the Beatles and the modernist writer Jorge Amado, Gil wrote about a love triangle that ends in murder at a Salvador amusement park. Performed for the first time during a music festival on Brazilian television in 1967, Domingo no Parque shocked the audience with its mix of traditional Brazilian music and the psychedelic guitars of Os Mutantes, the group that accompanied him on stage.

The song was included on his 1968 self-titled album and is considered the spark that exploded tropicália, a countercultural, ultra-cosmopolitan movement that also included visual art, poetry, theatre and cinema. Its anarchic vibrancy fed not just into art, but also anti-authoritarian politics that riled Brazil’s military dictatorship. Gil followed his debut with the cult album Tropicália: ou Panis et Circenses, released in the same year and featuring the best of the rest of the tropicalistas: Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Tom Zé and Os Mutantes. “Tropicália was very much in line with the late-60s zeitgeist: the struggle of students, the changes in customs, the ruptures,” recalls Gil. “This background has many similarities with the current moment – maybe that’s why tropicália still seems so current.”

The movement echoes in the music of new groups, such as O Terno and BaianaSystem, and has famous fans beyond Brazil. “This music, as sophisticated as popular, has served as an inspiration for newer generations of composers and performers,” writes David Byrne in the liner notes of the newly remastered version of the compilation Beleza Tropical, first released in 1989.

At the end of 1968, Gil and Caetano Veloso were arrested and jailed by the government, which was tightening the repression of its opponents. The official accusation was that they “incited the youth to rebellion”. In 1969, the duo were forced to leave the country (the farewell show in Salvador, held on the same day that Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon, was recorded and released three years later as the album Barra 69). They moved to London for two years in which Gil saw the Stones play live, discovered reggae, fell in love with Monty Python, recorded an album (with a version of Steve Winwood’s Can’t Find My Way Home), became a Chelsea supporter and participated in the talks that resulted in the creation of the Glastonbury festival in 1970.

“The festival was the result of a great articulation between the hippy community and the entire counterculture existing in England at that time. And as I attended these groups, I ended up being invited to participate in some meetings about a farmer who was offering his land for a big outdoor event,” he remembers with a smile. “So despite all the harshness of exile, I have very fond memories of London.”

He returns to the city next week for his We the People tour, with a backing band that includes sons, sons-in-law, daughters-in-law and grandchildren. Preparations were captured in the Amazon series At Home with the Gils; in five heartwarming episodes, the series shows tour rehearsals and a family retreat at the artist’s countryside house in Rio de Janeiro. Gil is always the calm centre of everything.

Gil says that over the years he got used to having cameras around him, “but being filmed with the whole family, with my children and grandchildren, was a novelty. Above all, this series serves as a document so that I can, at some point in my life, go back and see my two granddaughters growing up.”

Another new project is The Rhythm de Gil, an online exhibition on Google Arts & Culture. With 41,000 images and 900 videos, it pes deep into his history and features a big coup: a long-lost album.

The government’s hostility towards him eased a little in the early 70s and Gil negotiated his return to Brazil in 1972, notching up a series of successful albums. In 1982, the head of Warner Music Brasil persuaded him to record an album in English. Gil recorded nine songs – including one with Roberta Flack – during two weeks in a studio on Broadway in New York, but on his return to Brazil he decided to shelve it. “It was a good album, with excellent musicians, with whom I had a great rapport,” he says. “But I thought it lacked a Brazilian flavour.”

The untitled album was long assumed lost: the master recordings disappeared from the record company’s files and Gil fell out of touch with its producer, Ralph MacDonald. Then, in 2019, the nine songs were found on a cassette tape, gathering dust in the basement of Gil’s production company in Rio de Janeiro, during research work for the Google archive project.

“Finding this album after 40 years was something extraordinary,” Gil says. “It reminded me of that moment, hearing in my voice again that effort to sing English correctly. This re-encounter made me appreciate it in a way I couldn’t back then. It is one of the beauties of this project – it recycles all that the things I’ve done in my career and relaunches it in another plane of possibilities.”

When he gets back from the tour, he will release a collection of NFTs inspired by the visionary lyrics of Futurível, a song from the 1969 album Cérebro Eletrônico, written when he was in prison (“You’ll be transmuted into energy / Your second humanoid stage begins today / Keep calm, let’s start the broadcast / My system will change your dimension”). He will keep on making music, too – recently, he has collaborated with the group As Ganhadeiras de Itapuá, the reggae collective Digitaldubs and the rapper Emicida. At 80, Gil assures me that he still finds beauty in musical creation.

“The artist who is inspired by poetry and the creative challenge of the sung word has always something to say. And I like this embroidery – I like to sew words into the tissue of music. So, until the forces that provide this work disappear, I will keep on answering the request of that young singer who wants a collaboration, or that new author who asks for lyrics. As the saying goes: as long as there’s bamboo, there’s an arrow.”