The top brass: Ahead of two dedicated Proms, can brass bands finally move beyond the clichés?

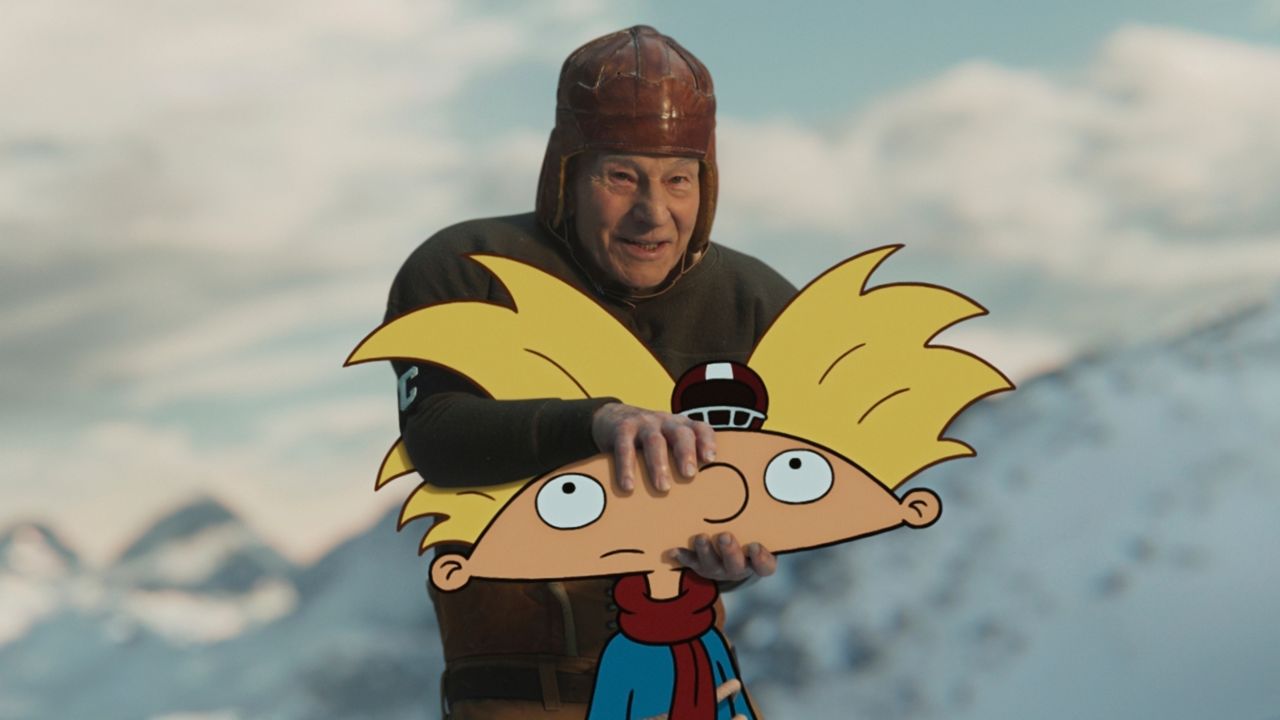

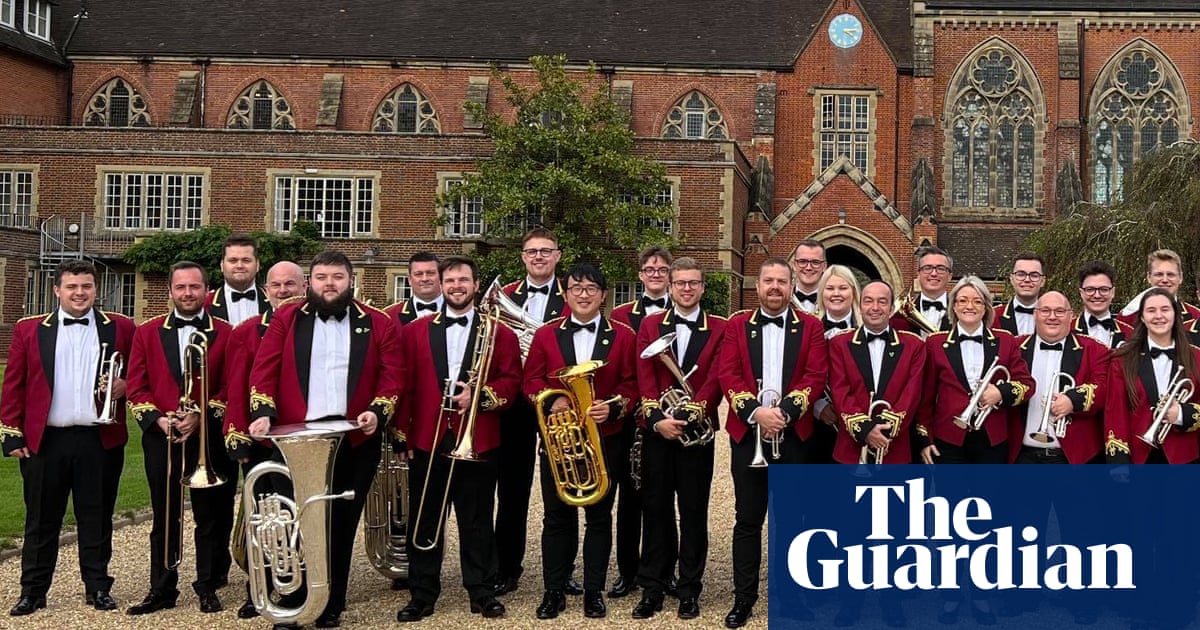

It’s quite a feat for a British ensemble older than the Proms to be making its debut at this year’s festival, but such is the case of Tredegar Town Band. Formally constituted in 1876, and with a performing CV stretching from Rambert Ballet to Matthew Warchus’s Bafta-winning film Pride, there’s a sense of making up for lost time with not one, but two Tredegar Proms this week . First, the band teams up with BBC National Orchestra of Wales and Ryan Bancroft for Gavin Higgins’ massive Concerto Grosso for Brass Band and Orchestra, then there’s a late-night Prom of their own the following evening.

You have to go back to 1989 and Charles Groves with the National Youth Brass Band for the last time the BBC Proms dedicated an entire concert to brass band music. Why the wait? “I wonder if it’s an image problem,” Higgins says, “and people still think it’s a bit twee, that brass bands are just the Hovis advert. I also think some assume that, because it’s amateur, essentially, that means it’s not going to be as good.”

This couldn’t be further from the truth. This is music of tremendous dexterity and huge power with the potential to overwhelm when heard live, something Higgins’ multi-ensemble composition – the first Proms commission of its kind – augments with added orchestral oomph.

But brass bands’ enduring image is a difficult one to reckon with for those questioning what “banding” (a popular collective term that suggests a holistic process similar to Christopher Small’s “musicking”) means among Britain’s network of music makers today. The UK’s brass band movement is inextricably linked with a well-established cluster of symbols. From its roots in heavy industry, to today’s collection of uniforms, crests, mottoes and banners, and regular appearances on bandstands and at union rallies, there’s a danger of it becoming shackled by history, particularly as the traditional links to vocation have dissolved.

“Brass bands are no longer a preserve of the working class,” Higgins says. (That banding has been a traditionally working-class activity is perhaps chief among the reasons for the form’s historic neglect by Proms programmers.) Like many of the composers now writing regularly for bands, Higgins’ family were all involved in the local band; banding “just happened” to him, first picking up the cornet followed by the tenor horn. “A lot of working-class people are still doing it, but Tredegar have lawyers in the band, doctors, people who work for the NHS, all sorts.”

Band musicians never complain about what you put in front of them. No one ever says, ‘This is really difficult.’ It’s the opposite.

But musically speaking at least, the traditional image of brass bands is at odds with the decidedly untraditional feats of previous Proms performances. When they have appeared on Proms programmes, bands have been adventurous advocates for new music, with scores by Harrison Birtwistle – himself from a military band background – Hans Werner Henze and George Benjamin featuring alongside more conventional fare. Holst’s A Moorside Suite, Elgar’s Severn Suite and Percy Grainger’s Seventeen Come Sunday softened the blow of Birtwistle’s caustic Grimethorpe Aria in first half of a historic 1974 Prom shared with the BBC Concert Orchestra and the BBC Singers. “Band musicians never moan or complain about what you put in front of them,” Higgins says. “No one ever says, ‘This is really difficult.’ It’s the opposite. They either say, ‘Can you make it a bit more challenging for us?’ Or they go ‘Well, we need to just go and practise it’. It feels like you can just write whatever you want.”

The Albert Hall is itself no stranger to brass bands. Since the end of the second world war, it’s been the venue for the finals of the National Brass Band Championships, which sees 20 qualifying bands travel to Kensington every October to perform their own rendition of a “test piece” – a taxing composition designed to reveal the flaws in every band’s technique. Imagine 20 orchestras lining up to deliver the best version of a Strauss tone poem, and you get a flavour of the scrutiny on show.

Brass band contesting is certainly idiosyncratic – an adjudicator sits behind a curtain to ensure impartiality, as the same piece of music is performed back-to-back. The moment of victory is immortalised in the finale of the film Brassed Off, with the fictional Grimley Colliery Band’s performance of the William Tell Overture harking back to Grimethorpe’s winning performance of Philip Wilby’s The New Jerusalem in 1992, just weeks after the village’s pit was announced as one earmarked for closure.

Yet the blue riband event in the contesting calendar is struggling, says Iwan Fox, editor of brass band magazine 4barsrest, and president of Tredegar Band. “There used to be a time when you could only get a ticket for that event through one of the ticket touts outside.” The last championships sold well under half its allocated tickets, a Covid-induced shortfall masking a gradual decline in interest. Formerly the nirvana for all standards of bands, now only the elite level competes at the Albert Hall, with the remaining four leagues instead performing at Cheltenham Racecourse.

There are other areas in which the banding movement is struggling, too. Away from the big-hitters such as Tredegar and the Cory Band (the south Wales outfit who have dominated the brass banding world rankings for the past decade), just five bands competed in the usually bustling Fourth Section, well under half the number in the same contest 10 years ago. “It’s the usual reasons,” Fox says. “Cuts in education, Covid-19, and the decline of peripatetic music services. The end result was that the foundations [of the banding structure] was the hardest hit.” There’s hope of a turnaround in this traditional brass band stronghold though, with the Welsh government’s new music service offering children the opportunity to learn musical instruments from September. “Hopefully the low point has been reached,” Fox says.

Higgins’ piece acknowledges banding’s roots with movement titles such as Coal and Class (if there’s one thing brass bands love, it’s an extra-musical narrative). But is that wise, for a movement keen to dispel stereotypes? “I don’t know if it’s good or bad, but I think you can’t really get away from it,” Higgins says. “It’s music that came out of pits, mines and industrial buildings. Brass band music is genuinely like a folk music for this country.”

The world premiere of Gavin Higgins’ Concerto Grosso for Brass Band and Orchestra is at the Proms on 8 August; Late-Night Brass – the Tregedar Band Prom is on Tuesday 9 August at 10.15pm