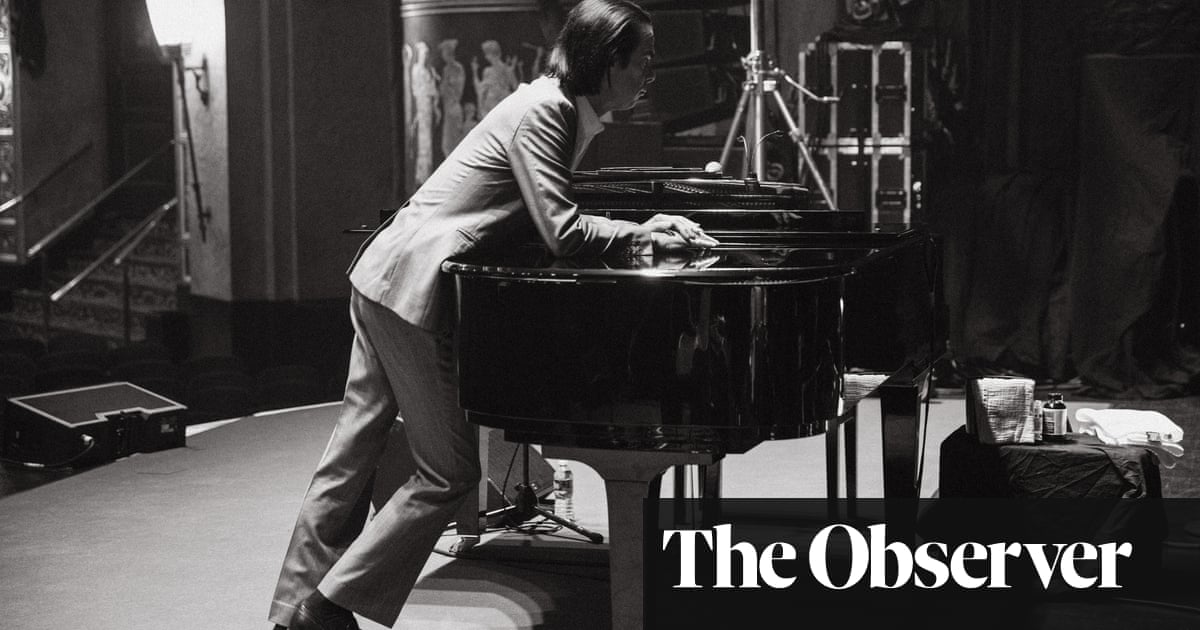

‘Songs are little dangerous bombs of truth’: Nick Cave and Sean O’Hagan – an exclusive book extract

In the early, anxious weeks of the first Covid lockdown in March 2020, Nick Cave and I spoke regularly on the phone. I have known Nick for more than 30 years, but in that time our paths tended to cross only fleetingly, often backstage at his concerts or when I was asked to interview him. The pandemic changed all that. With time on our hands and the world out of kilter, our phone chats turned into extended conversations about all manner of subjects, both esoteric and everyday. In that strange and heightened moment, the idea for a book was born.

Faith, Hope and Carnage is the end result of nearly 40 hours of recorded phone conversations that happened, off and on, between August 2020 and the summer of 2021. In the chapter that follows, Nick talks about the predictive, even uncannily prophetic nature of certain songs, the vulnerability that attends songwriting, and his working relationship with his collaborator and friend, Warren Ellis. He speaks candidly about the capsizing nature of grief, but also the small, but transformative, acts of kindness that he experienced from strangers in the wake of the death of his son, Arthur, and the “impossible realm” he entered while making his acclaimed album, Ghosteen.

SO’H: I was just listening to your 2016 album Skeleton Tree again, and remembering when I first heard it. Back then, I had assumed that most of the songs had been written after Arthur’s death [Cave’s son Arthur died in 2015 after a fall].

NC: No, the opposite in fact, but I can see why you might think that. I found that aspect of Skeleton Tree quite perplexing myself, to tell you the truth. I was disturbed by it, especially at the time. But when I think about it, it’s always been the way. I’ve always suspected that songwriting had a kind of secret dimension, without getting too mystical about it.

You actually touched on that idea back in 1998, in your lecture The Secret Life of the Love Song, that songs could be prescient in some way.

Yes, that’s right! If I remember correctly, I wrote about how my songs seemed to have a better handle on what was going on in my life than I did, but back then, it was more of a playful observation, comical, even.

Do you take the idea more seriously now?

Yes, I think so.

In the lecture, you used Far from Me from The Boatman’s Call (1997) as one example.

Yes. Over its three verses, that song describes the trajectory of a particular relationship I was in at the time. And then, in the final verse, it describes in detail the unhappy demise of that relationship. Now, in that instance, the song had written its final verse long before the relationship actually fell apart, so it was as if it had some secret knowledge or ability to look into the future. In the essay, I wrote about it in a lighthearted, whimsical way but, as I say, I’m not sure I feel that way any more.

My music does often seem to be one step ahead of what is actually going on in my life

“The song had written its final verse” is an intriguing way of putting it. Do you believe the song somehow wrote itself?

Well, that’s what it feels like with some songs. The more I’ve written, the harder it is to disregard the fact that so many songs seem to be some steps ahead of actual events. Now, I’m sure there are neurological explanations for that in the same way that there are for a phenomenon like deja vu, say, but it has become increasingly unnerving – the uncanny foresight of the song. And despite how it may appear from what I’m saying here, I’m really not a superstitious person. But the predictive aspect of the songs became too frequent, too insistent and too accurate to ignore. I don’t really want to make too much out of it except to say that I think songs have a way of talking into the future.

I tend to think my records are built out of an unconscious yearning for something. Whether that is a yearning for disruption, or a yearning for peace, very much depends on what I was going through at the time, but my music does often seem to be one step ahead of what is actually going on in my life.

I guess a song, like any work of art, is always going to unconsciously reveal something of the person who created it. If you write a truly honest song, it cannot help but be emotionally and psychologically revealing.

Yes, that’s true. Songs have the capacity to be revealing, acutely so. There is much they can teach us about ourselves. They are little dangerous bombs of truth.

Can you elaborate on the idea that songs often possess a latent meaning that is only revealed much later? It’s fascinating territory.

I guess I believe that there exists a genuine mystery at the heart of songwriting. Certain lines can appear at the time to be almost incomprehensible, but they nevertheless feel very true, very true indeed. And not just true, but necessary, and humming with a kind of unrevealed meaning. Through writing, you can enter a space of deep yearning that drags its past along with it and whispers into the future, that has an acute understanding of the way of things. You write a line that requires the future to reveal its meaning.

This imaginative space you’re describing sounds pretty intense. You’ve described it as unsettling before – were you specifically referring to Skeleton Tree?

Skeleton Tree certainly disturbed me, because there was so much in that record that suggested what went on to happen. It explicitly forecast the future, so much so that it was hard for many people to believe I had written almost all of the songs before Arthur died. The way that it spoke into the events that surrounded Arthur’s death was, at the time, very distressing. Now, I’m not really somebody who gets too engaged in this sort of thing. In fact, in the past, if someone started talking to me in this way, I would have dismissed him or her entirely. I think you and I are similar in that regard, yet at the same time, we are open to certain ambiguities in life. We cautiously acknowledge that there are, I don’t know, mysteries.

Yes, I never quite know what to do with those kinds of experiences, whether to accept them or try to find a rational explanation for them – which is always somehow unsatisfying.

That’s very true. But after Arthur died, things intensified for me in that regard. I felt both unsettled and reassured by a preternatural energy around certain things. The predictive nature of the songs was a small part of that. In fact, Susie [Cave’s wife] became totally spooked by my songs. She has always seen the world in signs and symbols, but even more so since Arthur died. For me, her openness and layered understanding of things is one of her most deeply attractive qualities.

Do you feel able to talk some more about the nature of that “preternatural energy” you felt? Was it akin to a heightened state of awareness?

Well, after Arthur died, the world seemed to vibrate with a peculiar, spiritual energy, as we’ve talked about. I was genuinely surprised by how susceptible I became to a kind of magical thinking. How readily I dispensed with that wholly rational part of my mind and how comforting it was to do so. Now, that may well be a strategy for survival and, as such, a part of the ordinary mechanics of grief, but it is something that persists to this day. Perhaps it is a kind of delusion, I don’t know, but if it is, it is a necessary and benevolent one.

If so, that kind of magical thinking is a strategy for survival that a lot of people use. Some sceptics might say it is the very basis of religious belief.

Yes. Some see it as the lie at the heart of religion, but I tend to think it is the much-needed utility of religion. And the lie – if the existence of God is, in fact, a falsehood – is, in some way, irrelevant. In fact, sometimes it feels to me as if the existence of God is a detail, or a technicality, so unbelievably rich are the benefits of a devotional life. Stepping into a church, listening to religious thinkers, reading scripture, sitting in silence, meditating, praying – all these religious activities eased the way back into the world for me. Those who discount them as falsities or superstitious nonsense, or worse, a collective mental feebleness, are made of sterner stuff than me. I grabbed at anything I could get my hands on and, since doing so, I’ve never let them go.

That’s completely understandable. But even in the most ordinary times, all those things you mention – sitting in silence in a church, meditating, praying – can be helpful or enriching even to a sceptic. Do you know what I mean? It’s as if the scepticism somehow makes those moments of reflection even more quietly wondrous.

Yes, there is a kind of gentle scepticism that makes belief stronger rather than weaker. In fact, it can be the forge on which a more robust belief can be hammered out.

When you came to perform Skeleton Tree, was that also unsettling for you?

Well, it became suddenly very difficult to sing those songs. I mean, without stating the obvious, the very first line of the first song on that record, Jesus Alone, begins with the lines: “You fell from the sky and landed in a field near the River Adur.” It was hard to hear and to sing – and hard to fathom how I had come to write a line like that given the events that followed. And the record is full of instances like that.

I’m aware I might be flailing around a bit here, but what I’m basically trying to say is that maybe we have deeper intuitions than we realise. Maybe the songs themselves are channels through which some kind of greater or deeper understanding is released into the world.

Could it even be that the heightened imaginative space you enter when you write a song is by its very nature revelatory? Poets like William Blake and WB Yeats certainly believed that. I doubt they would have had any problem with the prophetic or revelatory nature of songwriting.

No, I don’t think they would. And that ties in to what we’ve spoken about before, that there is another place that can be summoned through practice that is not the imagination, but more a secondary positioning of your mind with regard to spiritual matters. It’s complex, and I’m not sure I can really articulate it. The priest and religious writer Cynthia Bourgeault talks about “the imaginal realm”, which seems to be another place you can inhabit briefly that separates itself from the rational world and is independent of the imagination. It is a kind of liminal state of awareness, before dreaming, before imagining, that is connected to the spirit itself. It is an “impossible realm” where glimpses of the preternatural essence of things find their voice. Arthur lives there. Inside that space, it feels a relief to trust in certain glimpses of something else, something other, something beyond. Does that make sense?

I think to be truly vulnerable is to exist adjacent to collapse… In that place we can feel extraordinarily alive

I’m not sure, to be honest. Personally, I think I’d find that difficult to do.

Well, you’ve talked to me in the past about going into a church and lighting a candle for someone. That, for me, is like putting a kind of tentative toe into this particular space.

For me, lighting a candle for someone may be more an act of hope than faith. And I tend to think of it as one of the few residual traces of my Catholic upbringing.

Perhaps, but to go into a church and light a candle is quite a consequential thing to do, when you think about it. It is an act of yearning.

I guess so. And yet I struggle with what it means exactly. It may be that it just makes me feel better about myself.

I think at its very least it is a private gesture that signals a willingness to hand a part of oneself over to the mysterious, in the same way that prayer is, or, indeed, the making of music. Prayer to me is about making a space within oneself where we listen to the deeper, more mysterious aspects of our nature. I’m not sure that is such a bad thing to do, right?

No, not bad, but not rational, either. Then again, it may be that the most meaningful things are the most difficult to explain.

Yes, I think so. And I do think the rational aspect of ourselves is a beautiful and necessary thing, of course, but often its inflexible nature can render these small gestures of hope merely fanciful. It closes down the deeply healing aspect of pine possibility.

I have to say that I am slightly in awe of other people’s devotion. When I go into an empty church, it always feels meaningful somehow – and vulnerable – to just linger there for a moment or so. Do you know Larkin’s poem, Church Going, which is about that very thing?

Yes! “A serious house on serious earth it is.” And yes, there’s something about being open and vulnerable that is conversely very powerful, maybe even transformative.

For me, vulnerability is essential to spiritual and creative growth, whereas being invulnerable means being shut down, rigid, small. My experience of creating music and writing songs is finding enormous strength through vulnerability. You’re being open to whatever happens, including failure and shame. There’s certainly a vulnerability to that, and an incredible freedom.

The two are connected, maybe – vulnerability and freedom.

I think to be truly vulnerable is to exist adjacent to collapse or obliteration. In that place we can feel extraordinarily alive and receptive to all sorts of things, creatively and spiritually. It can be, perversely, a point of advantage, not disadvantage as one might think. It is a nuanced place that feels both dangerous and teeming with potential. It is the place where the big shifts can happen. The more time you spend there, the less worried you become of how you will be perceived or judged, and that is ultimately where the freedom is.

We’ve talked a lot about the shift in your songwriting style, but it’s surely a reflection of a much bigger and more profound shift of consciousness.

Yes, one that came out of a whole lot of things, but I guess it is essentially rooted in catastrophe.

Was there ever a point after Arthur’s death when you thought you might not be able to continue as a songwriter?

I don’t know if I thought about it in that way, but it just felt like everything had altered. When it happened, it just seemed like I had entered a place of acute disorder – a chaos that was also a kind of incapacitation. It’s not so much that I had to learn how to write a song again; it was more I had to learn how to pick up a pen. It was terrifying in a way. You’ve experienced sudden loss and grief, too, Sean, so you know what I’m talking about. You are tested to the extremes of your resilience, but it’s also almost impossible to describe the terrible intensity of that experience. Words just fall away.

Yes, and nothing prepares you for it. It’s tidal and it can be capsizing.

That’s a good word for it – “capsizing”. But I also think it is important to say that these feelings I am describing, this point of absolute annihilation, is not exceptional. In fact it is ordinary, in that it happens to all of us at some time or another. We are all, at some point in our lives, obliterated by loss. If you haven’t been by now, you will be in time – that’s for sure. And, of course, if you have been fortunate enough to have been truly loved, in this world, you will also cause extraordinary pain to others when you leave it. That’s the covenant of life and death, and the terrible beauty of grief.

Making Ghosteen, Warren and I were sort of mesmerised by the power of the work

What I remember most about the period after my younger brother died was a sense of total distractedness that came over me, an inability to concentrate that lasted for months. Did you experience that?

Yes, distraction was a big part of it, too.

We talked earlier about the act of lighting a candle, and that for me was the only thing that could still my mind. It was as if peace had descended if only for a few moments.

Stillness is what you crave in grief. When Arthur died, I was filled with an internal chaos, a roaring physical feeling in my very being as well as a terrible sense of dread and impending doom. I remember I could feel it literally rushing through my body and bursting out the ends of my fingers. When I was alone with my thoughts, there was an almost overwhelming physical feeling coursing through me. I have never felt anything like it. It was mental torment, of course, but also physical, deeply physical, a kind of annihilation of the self – an interior screaming.

Did you find a way to be still even for a few moments?

I had been meditating for years, but after the accident, I really thought I could never meditate again, that to sit still and allow that feeling to take hold of me would be some form of torture, impossible to endure. And yet, at one point, I went up to Arthur’s room and sat there on his bed, surrounded by his things, and I closed my eyes and meditated. I forced myself to do it. And, for the briefest moment in that meditation, I had this awareness that things could somehow be all right. It was like a small pulse of momentary light and then all the torment came rushing back. It was a sign and a significant shift.

But when you mentioned that sense of constant distractedness, I was thinking about how, after Arthur died, there was a raging conversation going on in my head endlessly. It felt different to normal brain chatter. It was like a conversation with my own dying self – or with death itself. And, in that period, the idea that we all die just became so fucking palpable that it infected everything. Everyone seemed to be at the point of dying.

You sensed that death was all around you, just biding its time?

Exactly. And that feeling was very extreme for Susie. In fact, she kept thinking that everyone was going to die – and soon. It was not just that everyone eventually dies, but that everyone we knew was going to die, like, tomorrow. She had these absolute existential freefalls that were to do with everyone’s life being in terrible jeopardy. It was heartbreaking.

But, in a way, that sense of death being present, and all those wild, traumatised feelings that went with it, ultimately gave us this weird, urgent energy. Not at first, but in time. It was, I don’t know how to explain it, an energy that allowed us to do anything we wanted to do. Ultimately, it opened up all kinds of possibilities and a strange reckless power came out of it. It was as if the worst had happened and nothing could hurt us, and all our ordinary concerns were little more than indulgences. There was a freedom in that. Susie’s return to the world was the most moving thing I have ever witnessed.

In what way?

Well, it was as if Susie had died before my eyes, but in time returned to the world.

You know, if there is one message I have, really, it concerns the question all grieving people ask: Does it ever get better? Over and over again, the inbox of the Red Hand Files [an online forum Cave uses to respond to questions from fans] is filled with letters from people wanting an answer to that appalling, solitary question. The answer is yes. We become different. We become better.

How long did it take before you got to that point?

I don’t know. I’m sorry, but I can’t remember. I don’t remember much of that time at all. It was incremental, or it is incremental. I think it was because I started to write about it and to talk about it, to attempt to articulate what was going on. I made a concerted effort to discover a language around this indescribable but very ordinary state of being.

To be forced to grieve publicly, I had to find a means of articulating what had happened. Finding the language became, for me, the way out. There is a great deficit in the language around grief. It’s not something we are practised at as a society, because it is too hard to talk about and, more importantly, it’s too hard to listen to. So many grieving people just remain silent, trapped in their own secret thoughts, trapped in their own minds, with their only form of company being the dead themselves.

Yes, and they close down and become numbed with grief. In your case, I wondered at the time if you were even aware of the depth of people’s responses to Arthur’s death? The incredible surge of empathy directed towards you.

Well, as far as the fans were concerned, yes. They saved my life. It was never in any way an imposition. It was truly amazing. And what you remember ultimately are the acts of kindness.

Yes, the small things that people say or do are often the things that stay with you.

So true, the small but monumental gesture. There’s a vegetarian takeaway place in Brighton called Infinity, where I would eat sometimes. I went there the first time I’d gone out in public after Arthur had died. There was a woman who worked there and I was always friendly with her, just the normal pleasantries, but I liked her. I was standing in the queue and she asked me what I wanted and it felt a little strange, because there was no acknowledgment of anything. She treated me like anyone else, matter-of-factly, professionally. She gave me my food and I gave her the money and – ah, sorry, it’s quite hard to talk about this – as she gave me back my change, she squeezed my hand. Purposefully.

It was such a quiet act of kindness. The simplest and most articulate of gestures, but, at the same time, it meant more than all that anybody had tried to tell me – you know, because of the failure of language in the face of catastrophe. She wished the best for me, in that moment. There was something truly moving to me about that simple, wordless act of compassion.

Such a beautifully instinctive and understated gesture.

Yes, exactly. I’ll never forget that. In difficult times I often go back to that feeling she gave me. Human beings are remarkable, really. Such nuanced, subtle creatures.

Did writing songs help you work your way through your grief and trauma?

That came much later. Before that happened, I think taking Skeleton Tree on the road was in its way a form of public rehabilitation. And doing the In Conversation tour was extremely helpful. I learned my own way of talking about grief.

When I heard you were doing the In Conversation events, I wasn’t sure how they would play out. Just the act of allowing people to ask you whatever they wanted, however inconsequential or profound, seemed risky. Was it a tightrope walk?

God, yes. When I look back, it was a really strange time to do something like that, because I was so weakened by the circumstances I found myself in. But it was a deeply intuitive decision to just put myself out there, come what may. You have to understand that there was an element of madness to the whole thing. I was living in this “impossible realm”. To be honest, I really had no idea what I was doing. I found out how to do it by doing it.

Looking back, I think the constant articulation of my own grief and hearing other people’s stories was very healing

So you entered the “impossible realm” each time you walked on stage to take people’s questions?

Very much so, and even before I went on stage. That is where I felt Arthur was really with me. We sat backstage with each other, talked to each other, and when I went on stage I felt a very strong, supporting presence and also an enormous strength – his hand in mine. It actually felt like the hand of the woman who had reached out to me in Infinity – as if her hand was somehow his hand. I felt I’d longed him to life. It was very strong and very powerful.

I had no idea it was that intense – and transformative.

It was. I did it every night and, through doing it, found a kind of invincibility through acute vulnerability. I was not in any way wallowing in my situation or exploiting it. I was rather matter-of factly explaining the place in which I’d found myself. I was attempting to help people, and receiving help, in return.

There was definitely something communally powerful about those In Conversation events.

Well, they were accepted in good faith. Often people opened up in deeply moving ways. It was like giving them a space to do that. And I found a strength and confidence that I could just do this potentially dangerous thing and who cares if it works or doesn’t? I knew it would be risky, because I was giving people permission to ask anything they wanted, but my thinking was, “What does it really matter what happens?” So that was a big shift in my thinking, for sure: to relinquish concern for the outcome of my artistic decisions and let the chips fall where they may. That idea has reverberated through everything I have done since.

So it was about being open and vulnerable, but also defiant in the face of catastrophe?

Yes, and that is a powerful place to be, because there was nothing that anyone could ask that I couldn’t handle in some kind of way. Looking back, I think the constant articulation of my own grief and hearing other people’s stories was very healing, because those who grieve know. They are the ones to tell the story. They have gone to the darkness and returned with the knowledge. They hold the information that other grieving people need to hear. And most astonishing of all, we all go there, in time.

Was making your 2019 album, Ghosteen, another way to enter even more deeply into that realm where Arthur was present?

I think so, yes. The Ghosteen experience came much later and making that record was as intense as things can get. But beautiful, you know, fiercely beautiful. It was energising in the most profound way. But also more than that.

There was a kind of holiness to Ghosteen that spoke into the absence of my son and breathed life into the void. Those days in Malibu making that record were like nothing I have ever experienced before or after, in terms of their wild potency. I can’t speak for Warren [Ellis, musician, composer and long time Cave collaborator], but I’m sure he would say something similar.

Was it in any way difficult to make?

Not difficult, we were just fixated. It was quite something, really, especially the Malibu sessions, where we just lived in the studio. We slept in a house nearby. The studio itself was one room, with the control desk inside it. We slept little, working until we dropped, never leaving the grounds. Day in, day out.

How did you end up recording in Malibu?

It was Chris Martin from Coldplay’s studio and he let us use it while he went and recorded down the road somewhere else. It was an amazing gesture.

So you were cocooned in the Coldplay compound?

Yes. Although that sounds a lot grander than it was! It was an incredibly concentrated experience, terrifying in its intensity, but not creatively difficult, not at all. The opposite. We were sort of mesmerised by the power of the work.

When you talk about the intense atmosphere in the studio, was it intense only in a positive way?

Yes, in the best possible way. And Warren was just amazing. We’re both bad sleepers and I’d get up at some hideous hour in the morning after going to bed at some hideous hour in the night, and Warren would just be sitting there, in the yard, in his underwear, with his headphones on, just listening, listening, listening. Warren’s commitment to the project, his sheer application, was beyond anything I have ever witnessed.

Did he understand what you were doing without your having to communicate it to him?

We didn’t talk about these things, as such, but the nature of the songs was so close to the bone, it was clear. When you are making music together, conversation becomes at best an auxiliary form of communication. It becomes unnecessary, even damaging, to explain things.

It seems strange now to say it, but I also had this idea that perhaps I could send a message to Arthur. I felt that if there was a way to do that, this was the way. An attempt to not just articulate the loss but to make contact in some kind of way, maybe in the same way as we pray, really.

Yes, the whole record has a prayerful aspect.

It does, and in that respect it had an ulterior motive, a secondary purpose, insofar as it was an attempt to somehow bring whatever spirits there may be towards me through this music. To give them a home.

And to communicate something to Arthur?

Yes, to communicate something. To say goodbye.

I see.

That’s what Ghosteen was for me. Arthur was snatched away, he just disappeared, and this felt like some way of making contact again and saying goodbye.

Faith, Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Sean O’Hagan is published on 20 September by Canongate Books (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer, buy your copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply