Triangle of Sadness

There’s something about the idea of floating on the open sea with a bunch of strangers that feels vaguely ominous, and given the reputation cruises have as breeding grounds for stomach bugs and potential death traps, it’s surprising we don’t see more films that take place abroad them. Good news, then, for anyone who ever read David Foster Wallace’s ‘A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again’ and felt seen – Ruben Östlund shares your apprehension about ocean-based holidays.

The latest brash provocation from the director of Force Majeure and The Square concerns the passengers aboard a luxury cruise ship and charts the series of unfortunate events that throw them into disarray. The self-avowed Marxist captain, Thomas (Woody Harrelson), is drunk, a storm is closing in, and there are some unsavoury-looking characters lurking on a passing boat.

Nevertheless, jobbing model Carl (Harris Dickinson) and his influencer girlfriend Yaya (Charlbi Dean) are making the most of a free holiday. Their fellow passengers include a Russian manure entrepreneur (Zlatko Burić) and a German woman who’s recently suffered a stroke rendering her unable to say anything except the words “In den Wolken”. If Carl and Yaya feel out of place, this is superseded by a lingering argument about their relationship (which comprises the film’s short opening chapter), in which Carl calls Yaya out for never paying for dinner when they’re together. He expresses a desire to defy traditional gender roles within their relationship, though Yaya seems a little sceptical about the suggestion.

Luckily for them, circumstance leads to an immediate opportunity for some gender role reversal, as they soon find themselves shipwrecked and discover that the only competent member of their group is Abigail (Dolly De Leon), a Filipino toilet cleaner on the ship. Abigail, sick and tired of dealing with rude passengers, is heartily pleased to finally be the one in charge.

Östlund delights in juxtaposing his big political themes with toilet humour – the amount of vomit and faecal matter in this film really can’t be understated – and the three-act structure leaves the film backloaded, as it is at its most enjoyable once the crew and guests are shipwrecked and start to live out an off-kilter version of ‘Lord of the Flies’.

Even if the storyline needs work, Östlund’s visual creativity delights in a scene where the camera appears to move with the rocking of the ship on choppy waters. Dickinson is superb as the idealistic but empty-headed Carl, who decides the best way to survive is to find someone to provide for him. Dickinson offsets his indisputable handsomeness by playing up Carl’s crotchetiness – he’s an expressive performer, and in the purse of his lips or furrow of his brow he can fill in the blanks between the lines of Östlund’s broad-strokes script.

It’s certainly an enjoyable watch, though Östlund gestures towards big questions about gender and class pisions without making any truly bold statements. Instead, his characters noodle around inside increasingly outlandish scenarios, and the eventual ending feels rather abrupt after two hours of build-up.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

By becoming a member you can support our independent journalism and receive exclusive prints, essays, film recommendations and more.

<p>Published 26 Oct 2022

Related News & Content

-

Limit taxonomy terms added to a custom post type

Limit taxonomy terms added to a custom post type,I've created a Custom Post Type and a Custom Taxonomy. In WP Admin, how can I limit amount of taxonomy terms that are added to the custom post type? I want to add no more than one tag into the post. Tags: custom post types custom taxonomy limit stackexchange.com WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Query top level custom post in taxonomy

Query top level custom post in taxonomy,This is my first post, I'm a bit stuck. I have a custom post (dan) and taxonomy (dnas), with hierarchical categories. I want to make a query resulting in posts at toplevel (hoofdcategorie01, Tags: stackexchange.com taxonomy WordPress Development Stack Exchange wp query -

Gutenberg: Restrict Top Level Blocks, But Not Child Blocks

Gutenberg: Restrict Top Level Blocks, But Not Child Blocks,Background I've created a custom top level "page section" block, to work with my existing theme. I've like to restrict top level blocks to ONLY that one block. However, I don't want to di... Tags: block editor stackexchange.com WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

How do I load styles into the block editor admin screen?

How do I load styles into the block editor admin screen?,The core file 'load-styles.php' generates css styles. Some of the styles interfere with the block editor. I would like to pass in my own style rules that override the styles generated by 'load-styl... Tags: block editor stackexchange.com WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Installing WordPress in a subdirectory

Installing WordPress in a subdirectory,I am trying to install wordpress into a subdirectory of a website. I simply want to build the client's new site in this subdirectory, so a separate and new WP install in this subdirectory, and the... Tags: installation stackexchange.com WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Custom theme and plugin updating

Custom theme and plugin updating,History: I'm working on a project for a client that involves building 27 unique websites that are built on wordpress. I say unique, because (for reasons that are not worth going into here) they ar... Tags: automatic updates plugin development stackexchange.com theme development WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Rewrite nested urls for custom post type

Rewrite nested urls for custom post type,I have a problem with nested permalink. I have a structure of urls like that: Catalog -> Category -> Product My urls are: www.domain.com/catalogs (for archive catalog) www.domain.com/catal... Tags: custom post types stackexchange.com url rewriting WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Ajax not working to insert, query and result data

Ajax not working to insert, query and result data,On my site, through a form I send/register same information in database, do a SELECT/query and return it! Return the last table saved in database, just that user just entered on the form (along wit... Tags: Ajax database functions plugin development stackexchange.com WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Israel at war, day 204: Hamas airs video of Israeli hostages, one with U.S. citizenship

Israel at war, day 204: Hamas airs video of Israeli hostages, one with U.S. citizenship,Hamas Studying Israel's Response to Position on Cease-fire Talks Gaza Aid Shipments Resume From Cyprus IDF: Two Palestinians Killed After Firing on IDF Outpost in the West Bank Pro-Palestinian Protest Leader Banned From Columbia Campus Here's What You Need to Know 204 Days Into the War Tags: 2023 Israel Gaza War haaretz.com Israel News -

No, You Didn’t Hallucinate a New Normani Song

No, You Didn’t Hallucinate a New Normani Song,No, you didn’t hallucinate a new Normani song. She really dropped “1:59,” featuring Gunna, after a two-year drought. Tags: Keycat Keytags vulture.com -

Here’s to Our Favorite Tortured Poets

Here’s to Our Favorite Tortured Poets,Taylor Swift and her various modern idiots join a long line of pop-culture poets sanctimoniously performing soliloquies, from real-life figures (‘Shakespeare in Love’) to the fictional but equally tortured (‘Dead Poets Society’). Tags: Keycat Keytags vulture.com -

I’ll Show You The Inside Of 12 Disney Homes, All You Have To Do Is Tell Me Which Movie They’re From

I'll Show You The Inside Of 12 Disney Homes, All You Have To Do Is Tell Me Which Movie They're From,I believe in you. Tags: buzzfeed.com evergreen Keycat Keytags Movies Trivia trivia quiz -

Toyota’s Super Bowl Ad Relies on Car Challenges, Not Famous Faces

Toyota's Super Bowl Ad Relies on Car Challenges, Not Famous Faces,Toyota decided just weeks ago to run a Super Bowl commercial, and is betting on a spot that has no celebrities or special effects. Tags: Keycat Keytags Super Bowl Commercials Toyota variety.com -

Mexican film wins top prize at Moscow International Film Festival while major studios boycott Russia

Mexican film wins top prize at Moscow International Film Festival while major studios boycott Russia,A Mexican film has won the top prize at the Moscow International Film Festival which took place as major Western studios boycott the Russian market and as Russia’s war in Ukraine grinds into its third year Tags: 109702159 abcnews.go.com Article Entertainment Fairs and festivals General news Keycat Keytags Movies Russia Ukraine war World news -

Release the Beatles Jerk-off Cut

Release the Beatles Jerk-off Cut,Sam Mendes is making four Beatles movies, one for each Beatle. But if none of the movies include the legendary story of John and Paul’s days of group masturbation, Mendes will have blown his wad for naught. Tags: Keycat Keytags vulture.com -

Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson confronts history at US pavilion as its first solo Indigenous artist

Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson confronts history at US pavilion as its first solo Indigenous artist,Jeffrey Gibson’s takeover of the U.S. pavilion for this year’s Venice Biennale contemporary art show is a celebration of color, pattern and craft Tags: 109377793 abcnews.go.com Article Entertainment General news Indigenous people Keycat Keytags Race and ethnicity U.S. News visual arts World news -

There’s a Great Movie to Be Made About Bob Marley’s Story. One Love Is Not It.

There’s a Great Movie to Be Made About Bob Marley’s Story. One Love Is Not It.,Walking away from ‘Bob Marley: One Love,’ you may feel you know less about the great musician than you did going in. Tags: Keycat Keytags vulture.com -

A24 Reveals I Saw the TV Glow Trailer, Announces Star-Studded Soundtrack

A24 Reveals I Saw the TV Glow Trailer, Announces Star-Studded Soundtrack,A24 has shared the trailer for the upcoming horror film I Saw the TV Glow and announced the soundtrack with Phoebe Bridgers, Alex G, and Caroline Polachek,. Tags: consequence.net Keycat Keytags -

Tom Hanks to Narrate Masters of the Air Companion Doc, The Bloody Hundredth

Tom Hanks to Narrate Masters of the Air Companion Doc, The Bloody Hundredth,Apple TV+ has announced The Bloody Hundredth, a companion documentary to Masters of the Air narrated by Tom Hanks. It premieres on March 15th. Tags: consequence.net Keycat Keytags -

Benson Boone Eyes Second Week at No. 1 In U.K. With ‘BeautifulThings’

Benson Boone Eyes Second Week at No. 1 In U.K. With ‘BeautifulThings’,Olivia Rodrigo is on track for the week's highest debut with "Obsessed." Tags: billboard.com Keycat Keytags -

West Virginia Gov. Justice vetoes bill that would have loosened school vaccine policies

West Virginia Gov. Justice vetoes bill that would have loosened school vaccine policies,West Virginia Republican Gov. Jim Justice broke with the GOP-majority Legislature to veto a bill that would have loosened one of the country’s strictest school vaccination policies Tags: 108569448 abcnews.go.com Article Children General news Health Immunizations Keycat Keytags Medication Politics U.S. News -

Blondshell and Bully Team Up For New Single “Docket”

Blondshell and Bully Team Up For New Single “Docket”,Blondshell has teamed up with Alicia Bognanno of Bully for the newly released single "Docket." Listen to the track here. Tags: Keycat Keytags pastemagazine.com -

Carol Kirkwood stuns in figure-hugging dress amid BBC Breakfast technical chaos

Carol Kirkwood stuns in figure-hugging dress amid BBC Breakfast technical chaos,CAROL Kirkwood stunned in a figure-hugging dress amid a technical blunder. BBC Breakfast was flung into chaos this morning after a string of sound issues. However Carol, 61, was all smiles as she p… Tags: BBC BBC Breakfast BBC ONE Carol Kirkwood mirror.co.uk The Scottish Sun TV News TV UK daytime TV -

Families ‘to sue prison’ where loud inmates ‘terrorise kids’ with screaming

Families 'to sue prison' where loud inmates 'terrorise kids' with screaming,Residents living next door to a new prison who say their kids have to sleep wearing headphones and some leave during weekends due to the racket are threatening to sue the prison service Tags: mirror.co.uk Neighbours from hell prisons Scottish government The Mirror -

Doctor Strange’s Secret Wars Role May Be More Important Than You Thought – Looper

Doctor Strange's Secret Wars Role May Be More Important Than You Thought - Looper,According to entertainment leaker Alex Perez, Doctor Strange will find himself confronting his inner struggles as he headlines "Avengers: Secret Wars." Tags: Fiction Looper looper.com Marvel Cinematic Universe Science Star Wars The Universal Monsters franchise -

Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson confronts history at US pavilion as its first solo Indigenous artist

Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson confronts history at US pavilion as its first solo Indigenous artist,Jeffrey Gibson’s takeover of the U.S. pavilion for this year’s Venice Biennale contemporary art show is a celebration of color, pattern and craft Tags: 109377793 abcnews.go.com Article Entertainment General news Indigenous people Keycat Keytags Race and ethnicity U.S. News visual arts World news -

Mexican film wins top prize at Moscow International Film Festival while major studios boycott Russia

Mexican film wins top prize at Moscow International Film Festival while major studios boycott Russia,A Mexican film has won the top prize at the Moscow International Film Festival which took place as major Western studios boycott the Russian market and as Russia’s war in Ukraine grinds into its third year Tags: 109702159 abcnews.go.com Article Entertainment Fairs and festivals General news Keycat Keytags Movies Russia Ukraine war World news -

Sandra Oh reenacts funny ‘Princess Diaries’ scene for Anne Hathaway

Sandra Oh reenacts funny ‘Princess Diaries’ scene for Anne Hathaway,Sandra Oh re-created a beloved scene from "The Princess Diaries" to announce Anne Hathaway's recent appearance on "The Kelly Clarkson Show." Tags: Movies popculture today TODAY.com -

Bestselling author Emily Henry shares her latest book recommendations

Bestselling author Emily Henry shares her latest book recommendations,What is Emily Henry reading right now? She shares book recommendations. Tags: books popculture today TODAY.com -

Watch This Lucid EV Beat the Heck Out of a Tesla Model S in a Drag Race

Watch This Lucid EV Beat the Heck Out of a Tesla Model S in a Drag Race,On the whole, big andpowerful electric vehicles are stupidly quick, but some models are still faster than others. For a while, the Tesla Model S Plaid held that crown with its 1.99-second 0-60 mph time, but it has since been dethroned in the super-sedan segment by the Lucid Air Sapphire. The Tesla rival can hit […] Tags: Gizmodo Australia gizmodo.com.au -

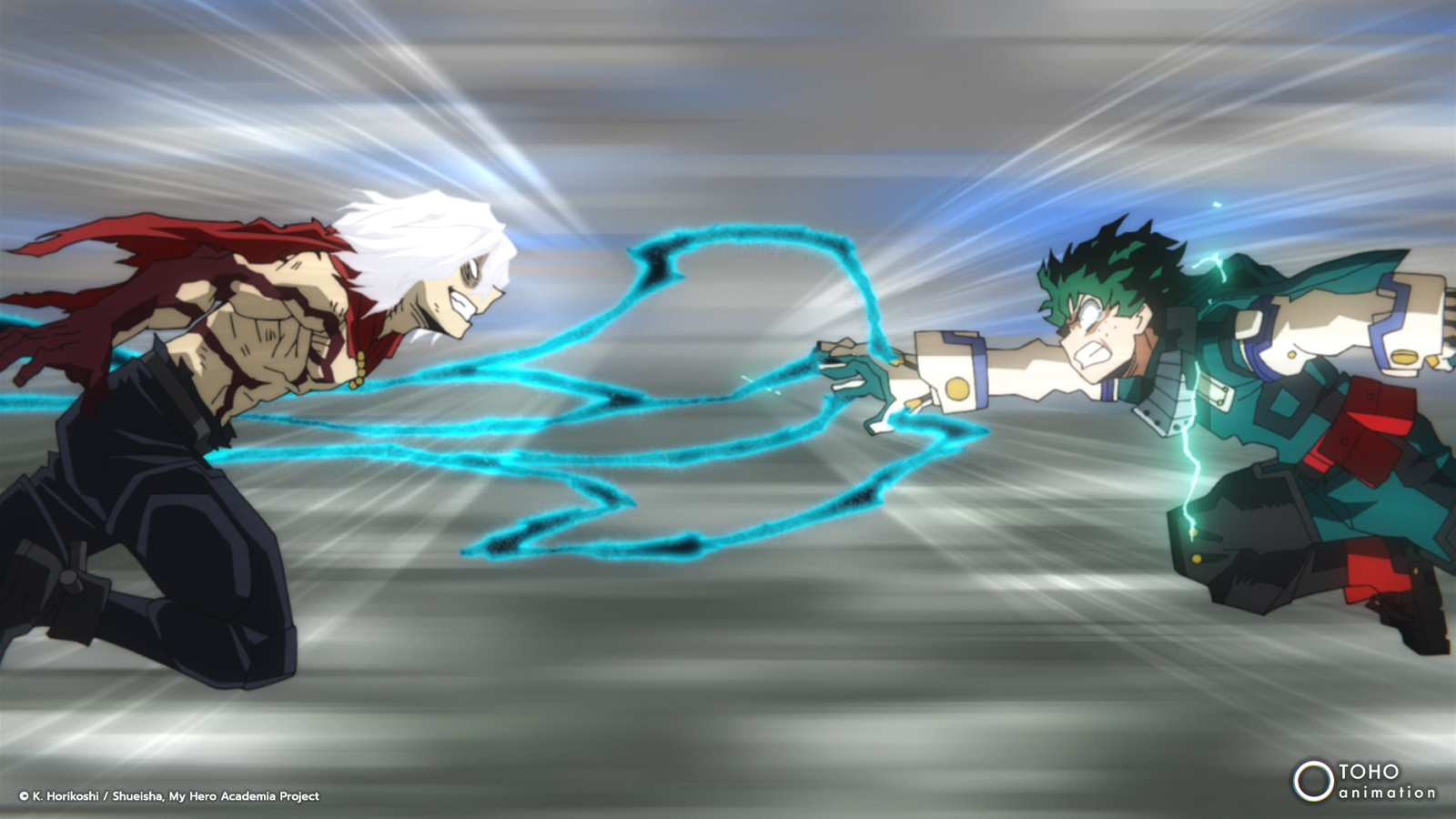

5 best anime to watch if you like My Hero Academia

5 best anime to watch if you like My Hero Academia,Here are five anime like My Hero Academia that will resonate with fans. These shows have major similarities with Boku no Hero. Tags: Anime anime like My Hero Academia boku no hero Haikyuu Hunter X Hunter ONE Esports oneesports.gg Ranking of Kings

Warning: file_get_contents(https://www.scienceradars.com/wp-output-content.php?pg=1&cat=&kw=&lvl=): Failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.1 526 in /home/wwwroot/xuenou.com/wp-content/themes/chromenews/template-parts/content.php on line 169

Warning: file_get_contents(https://www.bayuexiang.com/wp-output-content.php?pg=1&cat=&kw=&lvl=): Failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.1 526 in /home/wwwroot/xuenou.com/wp-content/themes/chromenews/template-parts/content.php on line 173

TrendRadars

The Most Interesting Articles, Mysteries and Discoveries