The Camera Is Ours review – pioneering women film-makers on the issues of their day

The Camera Is Ours review – pioneering women film-makers on the issues of their day

Here is a feature-length selection of documentary shorts from Britain’s pioneering women film-makers from the 1930s to the 1960s – a theatrical “touring version” from the Independent Cinema Office, taken from a larger assortment on the BFI’s two-disc DVD release.

The directors are very often tackling what were considered – by the male producers, that is – to be the “women’s issues” of the day: motherhood, family, hearth and home. Sometimes these are the explicit themes and sometimes they are a subtext. Two of the films are prefaced with content warnings about racism (though not sexism): a blackface minstrel show in Broadstairs is shown in one film and, in another on obstetric education for working-class women, someone is shown repeating the extraordinary superstition that drinking stout will “give you a black baby” – although, unlike the minstrels, this is clearly signposted in the film itself as bizarre and wrong.

Beside the Seaside (1935) by Marion Grierson, sister of John Grierson, is a sprightly, ambient evocation of the prewar seaside holiday, regarded without criticism or irony as a healthy restorative tradition. There’s a little of Jean Vigo’s À Propos de Nice in it. Another Grierson sister, Ruby, directed the drama-doc They Also Serve (1940), a paean to the home-front wives and mothers whose husbands were away in uniform, or perhaps too old for service. Quite a few of these films show, with unintentional poignancy, how stressed and prematurely aged the women had become. That is partly true of Birth-Day (1945), directed by Brigid Cooper and Mary Beales, about how working-class women of Scotland should speak to the soothing and reassuring professionals at the antenatal clinic. And it’s certainly true of Kay Mander’s Homes for the People (1945), a much brisker and less patronising work about the need for proper housing.

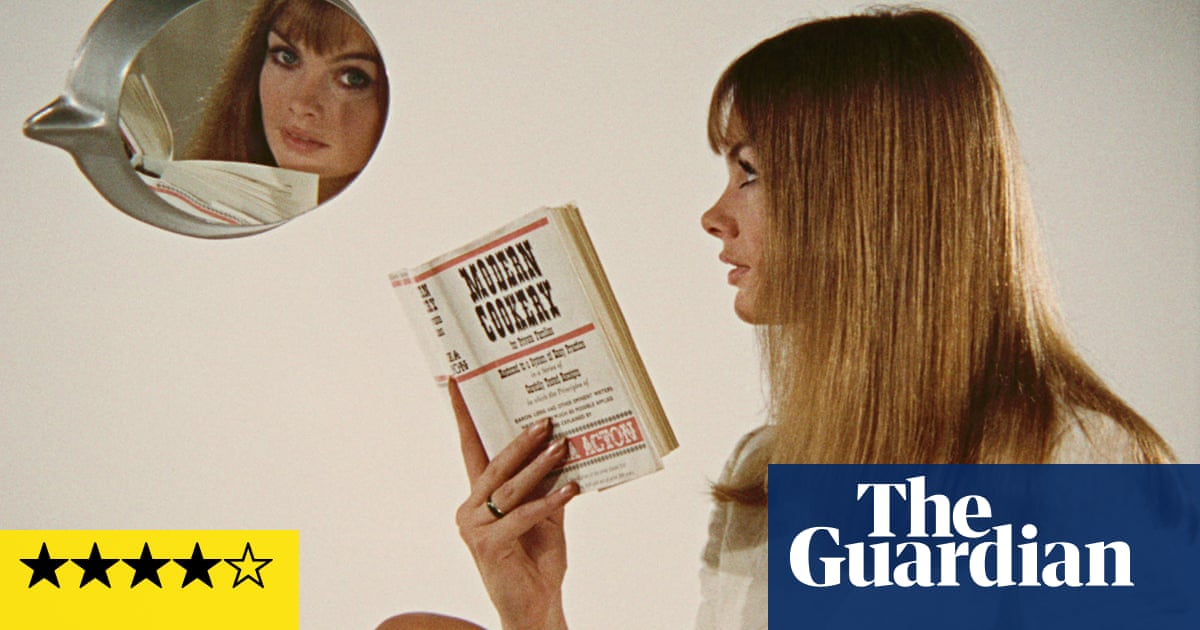

The selection finishes with the aspirational and slightly baffling Something Nice to Eat (1967), directed by Sarah Erulkar, sponsored by the Gas Board, with input from the Sunday Times magazine, evangelising for an ambitious kind of cooking inspired by the classy French. The film is a bit insufferable once it becomes clear that it is entirely addressed to ladies, and there is a curious section praising the ultra-modern kitchen. The one shown here comes with a lava lamp – great, for those who can afford it.

Related News & Content

-

How to display the_tags() as plain text

How to display the_tags() as plain text,the_tags by default is displaying as URL. I need to display it as plain text to insert inside HTML attribute. <?php $tag = the_tags(''); ?> <div class="image-portfolio" data-section... Tags: stackexchange.com tags WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Give to site admin the option to "skip confirmation email" when adding new user

Give to site admin the option to "skip confirmation email" when adding new user,in wordpress multisite when we give to site admin the option to add new users, site admin dont have the "checkbox" to add the new user without sending the user email with link activation (see the Tags: email verification multisite stackexchange.com users WordPress Development Stack Exchange -

Facing Hamas and Tehran, Israel is left with only vengeful madness | Opinion

Facing Hamas and Tehran, Israel is left with only vengeful madness | Opinion,Despite the Terrible Disaster on October 7, and the Failures It Exposed, Israel Is Still Convinced That the Image of the Mad Man Will Ensure Its Security -

Cairo ignored Israeli warnings about Gaza arms smuggling. Egypt’s apathy led to October 7 | Opinion

Cairo ignored Israeli warnings about Gaza arms smuggling. Egypt's apathy led to October 7 | Opinion,The October 7 War Is Not Just an Event Between Israel and Hamas, or Between Israel and Iran's Proxies. The War Is Rocking and Changing the Face of the Middle Ea -

Germany to give Holocaust survivors in Israel an extra $238 each because of Gaza war

Germany to give Holocaust survivors in Israel an extra $238 each because of Gaza war,'This Additional Symbolic Acknowledgment Payment by Germany to Holocaust Survivors in Israel Is a Message of Solidarity' Says Restitution Group Chief After Holocaust Survivors Impacted by October 7 Hamas Attack and Gaza War -

Israeli justice’s ruling reflects the structural discrimination against Palestinians | Editorial

Israeli justice's ruling reflects the structural discrimination against Palestinians | Editorial,High Court Justice Noam Sohlberg Denied an Appeal by the Shehadeh Family of Silwan and Ordered Them to Vacate the Home They Have Been Living in Since 1967 to Ac -

If Israel’s leadership sees humanity as a threat, we must insist on preserving it | Opinion

If Israel's leadership sees humanity as a threat, we must insist on preserving it | Opinion,Two Spaces in Israel Suffered Grievous Harm When Hamas Attacked on October 7, but to Some Extent, Each Space Was Harmed Independently. -

Satellite image shows damage from Iranian ballistic missile strike on Israeli air base

Satellite image shows damage from Iranian ballistic missile strike on Israeli air base,Photo Shows Damage to Taxiway Near C-130 Transport Planes at Nevatim Air Base, Which Sustained Four Ballistic Missile Hits in Iran's Overnight Attack on Israel -

Israeli airstrike kills seven aid workers in Gaza; IDF: ‘Tragic incident’

Israeli airstrike kills seven aid workers in Gaza; IDF: 'Tragic incident',Three of the Dead Have Been Identified, Including Two Foreign Aid Workers and Their Palestinian Driver; WCK: 'Humanitarian Aid Workers and Civilians Should Never Be a Target.' IDF: Conducting Review 'To Understand the Circumstances of This Tragic Incident' -

Carol Kirkwood stuns in figure-hugging dress amid BBC Breakfast technical chaos

Carol Kirkwood stuns in figure-hugging dress amid BBC Breakfast technical chaos,CAROL Kirkwood stunned in a figure-hugging dress amid a technical blunder. BBC Breakfast was flung into chaos this morning after a string of sound issues. However Carol, 61, was all smiles as she p… Tags: BBC BBC Breakfast BBC ONE Carol Kirkwood mirror.co.uk The Scottish Sun TV News TV UK daytime TV -

Families ‘to sue prison’ where loud inmates ‘terrorise kids’ with screaming

Families 'to sue prison' where loud inmates 'terrorise kids' with screaming,Residents living next door to a new prison who say their kids have to sleep wearing headphones and some leave during weekends due to the racket are threatening to sue the prison service Tags: mirror.co.uk Neighbours from hell prisons Scottish government The Mirror -

Doctor Strange’s Secret Wars Role May Be More Important Than You Thought – Looper

Doctor Strange's Secret Wars Role May Be More Important Than You Thought - Looper,According to entertainment leaker Alex Perez, Doctor Strange will find himself confronting his inner struggles as he headlines "Avengers: Secret Wars." Tags: Fiction Looper looper.com Marvel Cinematic Universe Science Star Wars The Universal Monsters franchise -

Blondshell and Bully Team Up For New Single “Docket”

Blondshell and Bully Team Up For New Single “Docket”,Blondshell has teamed up with Alicia Bognanno of Bully for the newly released single "Docket." Listen to the track here. Tags: Keycat Keytags pastemagazine.com -

I’m a clown for not trying Korean beauty secret for glowy skin sooner – don’t worry, I’m not putting cheese on my face

I’m a clown for not trying Korean beauty secret for glowy skin sooner – don’t worry, I’m not putting cheese on my face,A BEAUTY influencer has regrets about not trying out Korean beauty advice for glowy skin sooner. Although the trick can look a little strange at first, she assured viewers that she was not putting … Tags: Beauty beauty parlor Fabulous Food and drink Hair and Beauty medical health medicine style and fashion The Sun the-sun.com Tips tricks and life hacks -

Kristin Cavallari Slams Critics Saying Boyfriend Mark Estes Is 'Using' Her

Kristin Cavallari Slams Critics Saying Boyfriend Mark Estes Is 'Using' Her,Kristin Cavallari wants critics to know that she does not care what they say about her relationship with 24-year-old Mark Estes. Tags: AliciaSilverstone celebrity disney ElleKing Entertainment Hotphotos KristinCavallari KristinElizabethCavallari nationalgeographic.com Toofab -

Ex-Assistant Principal Faces Felony Charges for Ignoring Warning After Warning About Armed Six-Year-Old Shooter

Ex-Assistant Principal Faces Felony Charges for Ignoring Warning After Warning About Armed Six-Year-Old Shooter,Ebony Parker is facing eight felony child abuse charges for her alleged failure to respond to multiple school staff members' voiced concerns about a six-year-old student bringing a gun to the school in the hours before he opened fire in his first-grade classroom, shooting his teacher, Abby Zwerner. Tags: AlexanderLudwig celebrity Hotphotos Laurenludwig nationalgeographic.com News Toofab truecrime -

Wife who set fire to husband, a former deputy sheriff, and watched him burn before eventually calling 911 is convicted of murder

Wife who set fire to husband, a former deputy sheriff, and watched him burn before eventually calling 911 is convicted of murder,Evelyn Zigerelli-Henderson was convicted of killing her husband, a former county deputy sheriff, by setting him on fire in the back of their Pennsylvania home. -

Tyler Cameron Reveals If He Will Launch An OnlyFans

Tyler Cameron Reveals If He Will Launch An OnlyFans,Tyler Cameron has had fans begging him to launch an OnlyFans account -- he reveals whether he actually will. Plus, Tyler explains why he believes he has had so much success since his time on 'The Bachelorette' in 2019. Tags: nationalgeographic.com News reddit Toofab truecrime

Warning: file_get_contents(https://www.scienceradars.com/wp-output-content.php?pg=1&cat=&kw=&lvl=): Failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.1 526 in /home/wwwroot/xuenou.com/wp-content/themes/chromenews/template-parts/content.php on line 169

Warning: file_get_contents(https://www.bayuexiang.com/wp-output-content.php?pg=1&cat=&kw=&lvl=): Failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.1 526 in /home/wwwroot/xuenou.com/wp-content/themes/chromenews/template-parts/content.php on line 173

TrendRadars

The Most Interesting Articles, Mysteries and Discoveries

Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Fraudsters murdered elderly man, dumped his body, and moved into his home: Prosecutors

Hayden Panettiere Is Releasing A Memoir About Her Past Addiction Struggles

How to plan the ultimate island-hopping adventure in the Philippines