‘My Films Had So Much Anger’

More than three decades ago, John Woo reinvented the action movie. He did so not just with his deliriously choreographed action scenes, but with his unabashedly melodramatic tales of violent men who bonded with their adversaries. His revolutionary Hong Kong “heroic bloodshed” films — A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989), and Hard-Boiled (1992) being the best known — broke through in the West in the early 1990s, influencing everyone from James Cameron to Quentin Tarantino. Right around then, Woo himself came to the U.S., making his Hollywood debut with the Jean-Claude Van Damme-starring Hard Target (1993), a modest hit that has, over the years, come to be regarded as a classic.

At their best, Woo’s American pictures showcased his ability to blend mind-melting action scenes with a kind of romanticism and emotionality genre films often looked down on; in that sense, Face/Off (1997) remains unmatched. The mixture worked financially as well: Broken Arrow (1996), Face/Off, and Mission: Impossible 2 (2000) were all big hits. But then, Woo’s style of filmmaking seemed to vanish, as the world of action pided itself into gritty, self-important shakycam on one side and elaborate, VFX-infused fantasy and sci-fi on the other.

Now, it’s fair to say that we are undergoing a revival and re-appreciation of Woo’s work. The Criterion Collection recently released his 1979 film Last Hurrah for Chivalry. A Face/Off 4K comes out next month. (One for Hard Target came out a couple of years ago.) Most importantly, Woo has finished shooting a new film, Silent Night, starring Joel Kinnaman, his first American feature since 2003’s (underrated) Ben Affleck-starring Paycheck, and he’s preparing to shoot another. When he pops up on the Zoom window, the first thing I notice is an enormous poster of Jean-Pierre Melville’s Magnet of Doom (1963) on the wall behind him.

I see the Jean-Pierre Melville poster in the background.Yeah. He was my hero. I loved his movies. I stole from two of his movies, Le Samouraï and The Red Circle, when I made The Killer. He was the biggest influence on me.

When were you first exposed to his films? We didn’t have any kind of film school in Hong Kong, so we had to learn from movies and foreign film critics. We studied them in the library. We had a community, a group of young people who would get together and make experimental films. We watched great movies at the Italian, French, and British embassies. Art films were showing in commercial theaters back then. That was how we learned the movies. I learned so much from European films in my 20s.

How did you get into the film industry? It was tough for film-crazy young people like us to get into the business. If you didn’t have a relationship with anyone in the business, you’d never get a chance to work. I was lucky. In 1968, there was a film-studio manager who was the first one to study movies in Italy and had an open mind. When he came back to finish up as chairman of one of the biggest studios in Hong Kong, he hired young people like us into the business. My first job was script supervisor for a film. Later I changed to another studio, Shaw Brothers, where I worked with one of my favorite directors, Chang Cheh, as a script supervisor and assistant director. I worked for him for almost two years, then I got the opportunity to direct my first film when I was 27.

Probably the best-known film from your early period is 1979’s Last Hurrah for Chivalry, which just came out as part of the Criterion Collection. How did you develop the action scenes in the film? I learned so much from my great master, Chang Cheh — especially how he worked with his stunt coordinator and the way he used camera movement. When he passed away, the people who followed him for decades, like the stunt team, were all out of work. So I grouped them together again and made Last Hurrah for Chivalry as a tribute. I tried to pay tribute to Akira Kurosawa. I really liked the Chinese swordsmen in ancient times, who had the true spirit of chivalry. I was fascinated with four very famous assassins in ancient China and their code of honor. I used their story as a base, then created my kind of hero.

In Hong Kong back then, there was a lot of competition. While rewatching other movies, if we saw something we liked — a new fight technique or concept — we wanted to improve on it. I’ve never learned kung fu. I’ve never learned any sword-fighting. But I’m crazy about dancing and musicals. I wanted the action to look beautiful, exciting, and elegant. And I went with my instincts. Like, the character of the drunken swordsman [in Last Hurrah for Chivalry] was me! When I was young, I was a drunkard. But I believed I had a code of honor. I wanted to do good and defend justice.

I feel I was a little too ambitious. I was too young. I hadn’t learned enough. I think the dialogue is a little too cheesy.

In my movie, at the end, the two men have to work together, and the emotion — the love, hate, and everything — it’s all there in the fight. But I wanted to show some kind of humanity. In the film, the drunken swordsman sacrifices himself for a friend. That always moves me. Even when I was making gun-battle movies, like Hard Boiled or The Killer, they had that kind of spirit. That’s my philosophy of life. Life is beautiful as long as you have real friends.

How do you see Last Hurrah for Chivalry now?I still love the movie, but I feel I was a little too ambitious. I was too young. I hadn’t learned enough. I think the dialogue is a little too cheesy. When you understand Chinese, the dialogue is too modern. It doesn’t sound like a classic movie. Many of the dialogue scenes looked like they were shot in a police station — like you’re watching a play, not a movie. But in general, I still love the movie. Before Last Hurrah for Chivalry, I’d always wanted to make a movie like Le Samouraï. But the studio always said, “You just started. It’s too early to make that kind of movie. Those kinds of movies are poison. Nobody wants to watch them.” At the time, the most popular movies were what we called “fist” and “pillow” movies. The fist was kung-fu, martial-arts fighting. And the pillow was a sex film. So I was frustrated. All I could do was make some kind of kung-fu film and a comedy. I like comedy, but I don’t have that kind of passion. I made eight of them, but they didn’t look like comedies, because my films had so much anger.

Where did that anger come from?I had so much anger about society. Rich people were getting richer, and poor people were getting poorer. The criminals were nearly untouchable, and good people never got true justice. The studio still didn’t let me make the real movies I wanted to make. So I put all of my anger into the comedies. When people came to watch my movies, they didn’t know if they should laugh, cry, or be angry. But I don’t regret it, because I feel, as a filmmaker, you’ve got a duty to serve the truth inside your heart. No matter if it’s a comedy, action, or a love story, I’ve got to bring my true feelings into the film. I don’t want to hide and be happy. If I’m not happy, I don’t want to do something to try to please anybody.

Later, I met my good friend Tsui Hark, a brilliant, talented filmmaker. I recommended him to a new studio. Then, in 1985, because I had helped him start his career, he returned the favor and supported me to make A Better Tomorrow. I put all of the French elements into the film. At last, I really could do whatever I wanted.

That period from A Better Tomorrow and Bullet in the Head to The Killer and Hard Boiled was a pivotal time for you — when you developed this revolutionary style. How did that come about?Well, in the late ’70s, with the Hong Kong New Wave coming up, all of a sudden, the whole business changed. The fist and pillow movies didn’t work anymore. There was a young audience, a new generation, and they wanted something new. We had some open-minded financiers and producers who trusted us, which gave us a lot of creative freedom. And we knew our audience, because the market is so small: only Hong Kong, Taiwan, and some Chinatown theaters in foreign countries.

But for me, it was hard. I came from the old-time movies like the French New Wave. It was hard to talk to the crew about Federico Fellini, François Truffaut, Jean-Pierre Melville. It was hard to let people know what I was really thinking. That’s why I feel like a lot of our movies shot without a script. Like The Killer. There was no script. It was all in my mind. But this was a good thing as well, because I could control everything myself — like Stanley Kubrick. The studio gave me a reasonable budget, and I told them how many days for the shoot and what the story is about, then I could totally control the budget, crew, and everything. I love to shoot on soundstages. Every day, I just shut the door and made my own film. The financial people never came to the set, never asked anything. And the audience loved it.

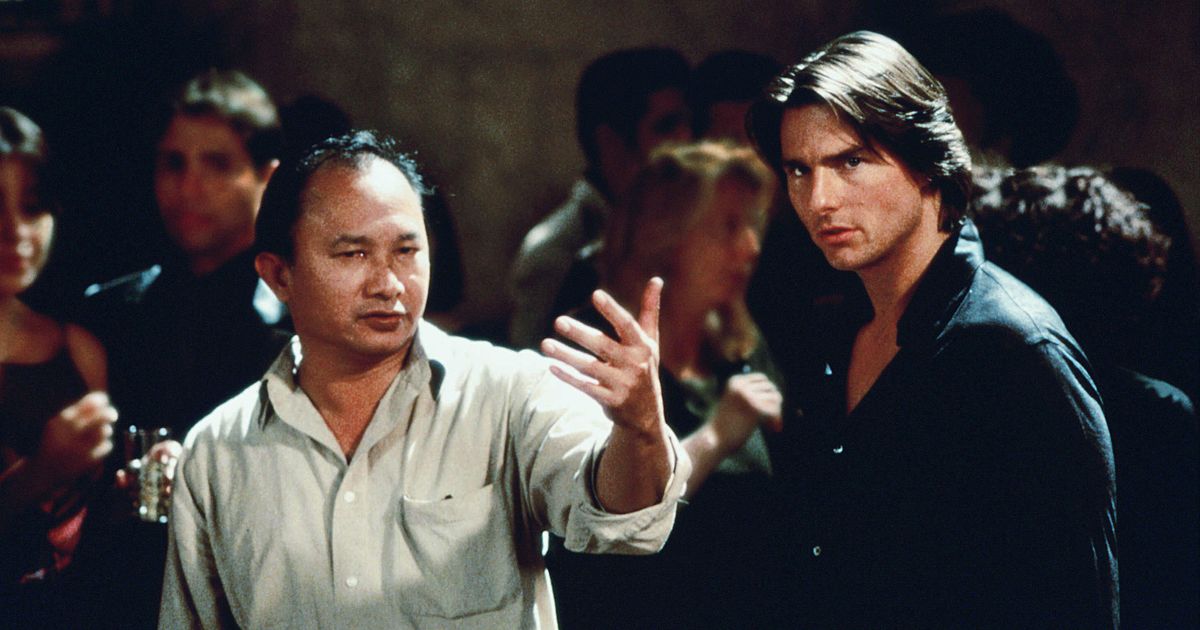

On the set of Face/Off (1997).Photo: Paramount/Courtesy Everett Collection

The boat chase at the end of Face/Off is spectacular, and one of the things I love about it is that you can see the stunt doubles’ faces. It’s not Travolta or Cage. That actually enhances the scene for me, because that tells us it’s not being faked. Yeah, I never like to hide it. The audience understands that the most dangerous action is usually played by the stunt guy. Tom Cruise likes to do all kinds of risky action scenes, but there are not many people like him. And I didn’t want to do digital faces. I just tried to maintain the beauty of the action. If a shot looks beautiful and stunning, I want to keep it. It’s about the film language. You can see, in my action scenes, I never like to do the quick cut or second camera.

One reason I like to keep making action movies is because I have a high respect for stunt people all over the world. I think they have a true spirit and great professional honor. If something is memorable, beautiful, or challenging, they love to do it. In some way, I feel they have the same qualities as a ballet dancer.

It sounds like you didn’t get that kind of creative freedom again, even though Face/Off was a huge hit. The others, they’re all right. Even if they gave me notes, they still let me make the last decision. The only thing they were concerned about was the violence — usually. “Oh, for the Hong Kong movie, you can shoot as much as you want, but in this country, can you cut it down a little bit? Not more than five shots instead of a hundred bullets in your film.” I understood, and I sympathized. I mean, in this country, there were some Asian gangsters robbing a jewelry store in an Asian area. When they caught them and asked them why they did that, they said, “We learned from John Woo movies.” They learned it from Bullet in the Head. This was many, many years ago, but I still feel pretty bad. So when the studio said it didn’t want to give any bad influences to younger people, I calmed down a little.

I didn’t feel I got old or anything like that. I just didn’t like the new changes.

Is there a film from your American period that you wish people would take another look at?Windtalkers. There were not many people who really understood that movie or liked it. It was not good timing. The movie had to be released in 2001. Then 9/11 happened, so they had to push it. They were so afraid audiences wouldn’t want to watch a war movie at that time. I had a conflict with the writers. I said, “My kind of movie is usually about friendship, respect, and honor.” But the writers didn’t feel good about that. They said, “The enemy is the enemy. The enemy has to be destroyed.” I tried to make it a human story. The audience didn’t expect a movie about friendship. But I’m still proud of that movie.

Your style of action filmmaking was so influential in the ’90s and 2000s, but then, in the mid-2000s or so, there was a move toward a harder, “realistic” handheld aesthetic. Did you sense that at the time? That’s when you went to China and did Red Cliff. Yeah, I sensed it. I didn’t like it. At the time, I couldn’t stand to see everyone doing the same thing and using the shaky camera and fast cuts. Even the drama movies were always using a handheld camera. I couldn’t read the actors’ faces. I couldn’t hear what they were saying. I couldn’t pay attention to their performances. I had a problem with that kind of style. Whenever I watched that kind of movie, whether in a theater or on DVD, whenever I saw the camera shake, I stepped out. I left the theater. I couldn’t stand it. I think it’s not a real movie. The reason I went to shoot a Chinese movie is because I had been asked to help Chinese movies have more of a world market. I didn’t feel I got old or anything like that. I just didn’t like the new changes.

You just shot another movie, Silent Night, is that correct?Yeah. Very interesting movie. The whole movie is without dialogue. It allowed me to use visuals to tell the story, to tell how the character feels. We are using music instead of language. And the movie is all about sight and sound. The budget was a little tight, and the schedule was tight, but it made me change my working style. Usually, for a big movie, a studio movie, we shoot a lot of coverage, then leave it to the cutting room. But in this movie, I tried to combine things without doing any coverage shots. I had to force myself to use a new kind of technique. Some scenes were about two or three pages, but I did it all in one shot.

It’s almost like you’re finally doing a musical. Yeah. Yeah. [Laughs]

How do you view your American period now? Is there anything you would have done differently if you had to do it all over again?I’ve learned a lot of things. I learned how to shoot an action scene with CGI and other technical things. I think all of us, including the actors, no matter if they’re American or Chinese — we all have the same kind of emotion and humanity. But in Hollywood, it feels safer, because everybody is so professional. In Hong Kong, they just shoot the movie even without a script. But I’m still learning. Every movie is a learning process for me. This is a great world. Everybody deserves to learn.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

![iFi's GO Bar Kensei Dongle DAC Supports K2HD Technology With Some Samurai Swagger [Updated] iFi's GO Bar Kensei Dongle DAC Supports K2HD Technology With Some Samurai Swagger [Updated]](https://i0.wp.com/cdn.ecoustics.com/db0/wblob/17BA35E873D594/33FF/45A11/QTXOLJR4xDKSNMMk2WlTgjaIlvSgcYpeU1xJzUwIoYs/ifi-go-bar-kensei.jpg?w=768&ssl=1)