All Light, Everywhere review – probing study of the weaponisation of surveillance tech

All Light, Everywhere review – probing study of the weaponisation of surveillance tech

‘Seeing is believing,” goes the old adage, and yet, for a film that investigates the intimate relationship between surveillance and the police state, Theo Anthony’s absorbing documentary chooses to begin with an eerie, unseeing image. The lens turned on the director’s own eyeballs, it inspects the optic nerve, which connects the eye to the brain but itself holds no visual information. Like the neurology of human perception, the recording devices used by police forces also sit on the edge of seeing and not seeing. By virtue of being mechanical, cameras – and the images they record – promise an unbiased visual access to truth, their representations of reality eliminating the fallibility of human emotions and prejudices.

Editing together a tour around Axon, a Taser company now specialising in body cameras, and training classes for the Baltimore police department, Anthony’s film exposes how these surveillance gadgets are designed for the protection of state interests rather than ordinary citizens. The point is made that this militarisation of the camera is nothing new: a line is drawn from modern surveillance technology to inventions in the early years of the moving image, including rifle cameras and criminal profile photography. All Light, Everywhere shows, too, how cinema, even its documentary form, has always been complicit in weaponising images.

While the effort put into research for this documentary is commendable, ultimately the aestheticisation of the information dampens its impact. Sonorous and hypnotic, the beautiful electronic score ends up transforming surveillance technology into an otherworldly phenomenon, when in reality its evil lies in its banality and invisibility. An epilogue showing Anthony’s film-making classes at a predominantly Black high school ends the film oddly; a subtitle tells us we can’t see the students’ footage because what happens inside the classroom cannot be “contained” by the film. In a film about state-produced images that dictate the course of justice, it is a strange decision to efface outsider voices.

Related News & Content

-

Tributes as Line of Duty star dies suddenly aged 59 as heartbroken wife pays tribute

Tributes as Line of Duty star dies suddenly aged 59 as heartbroken wife pays tribute,article" property="og:type" /><meta content="Line of Duty actor Brian James McCardie has died at the age of 59, his family has announced. -

How Israel continues to censor journalists covering the war in Gaza

How Israel continues to censor journalists covering the war in Gaza,Israel continues to restrict international journalists access to Gaza, and Palestinian reporters are being killed. -

Reality TV in the UK is almost dead – why The Traitors offers a last glimmer of hope

Reality TV in the UK is almost dead – why The Traitors offers a last glimmer of hope,Once huge ratings draws, reality TV shows are facing dwindling audiences in the UK and elsewhere. Is this the end of the genre, or can it adapt to survive? -

'Basement area' for sale in south London for just £5,000 – but you have to excavate the…

'Basement area' for sale in south London for just £5,000 - but you have to excavate the...,article" property="og:type" /><meta content="A "basement area" has been put up for sale in south London for only £5,000 - but it comes with a significant catch. -

Frank Field: a Labour MP who dedicated his life to fighting poverty and epitomised the politics of character

Frank Field: a Labour MP who dedicated his life to fighting poverty and epitomised the politics of character,The Labour MP was friends with Margaret Thatcher, but certainly didn’t agree that there’s ‘no such thing as society’. -

Beyoncé and Dolly Parton’s versions of Jolene represent two sides of southern femininity

Beyoncé and Dolly Parton’s versions of Jolene represent two sides of southern femininity,A young white southern belle asks a woman not to cheat with her man while an older Black southern queen warns a woman against cheating with her husband. -

Canary Islands plead with British holidaymakers not to cancel trips despite surge in…

Canary Islands plead with British holidaymakers not to cancel trips despite surge in...,article" property="og:type" /><meta content="The Canary Islands tourism minister has pleaded with British holidaymakers not to cancel their holidays despite anti-tourism protests set to take place. -

Scotland’s hate crime law: the problem with using public order laws to govern online speech

Scotland’s hate crime law: the problem with using public order laws to govern online speech,It is difficult to argue that online comments can amount to criminal offences that threaten public order. -

Purple Hibiscus: Ibrahim Mahama’s Barbican installation wraps the brutalist building in bright cloth and reveals a hidden history

Purple Hibiscus: Ibrahim Mahama’s Barbican installation wraps the brutalist building in bright cloth and reveals a hidden history,The bright pink fabric swaying gently in the wind stands in stark contrast to the grey tones of the brutalist architectural complex. -

Carol Kirkwood stuns in figure-hugging dress amid BBC Breakfast technical chaos

Carol Kirkwood stuns in figure-hugging dress amid BBC Breakfast technical chaos,CAROL Kirkwood stunned in a figure-hugging dress amid a technical blunder. BBC Breakfast was flung into chaos this morning after a string of sound issues. However Carol, 61, was all smiles as she p… Tags: BBC BBC Breakfast BBC ONE Carol Kirkwood mirror.co.uk The Scottish Sun TV News TV UK daytime TV -

Families ‘to sue prison’ where loud inmates ‘terrorise kids’ with screaming

Families 'to sue prison' where loud inmates 'terrorise kids' with screaming,Residents living next door to a new prison who say their kids have to sleep wearing headphones and some leave during weekends due to the racket are threatening to sue the prison service Tags: mirror.co.uk Neighbours from hell prisons Scottish government The Mirror -

Doctor Strange’s Secret Wars Role May Be More Important Than You Thought – Looper

Doctor Strange's Secret Wars Role May Be More Important Than You Thought - Looper,According to entertainment leaker Alex Perez, Doctor Strange will find himself confronting his inner struggles as he headlines "Avengers: Secret Wars." Tags: Fiction Looper looper.com Marvel Cinematic Universe Science Star Wars The Universal Monsters franchise -

Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson confronts history at US pavilion as its first solo Indigenous artist

Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson confronts history at US pavilion as its first solo Indigenous artist,Jeffrey Gibson’s takeover of the U.S. pavilion for this year’s Venice Biennale contemporary art show is a celebration of color, pattern and craft Tags: 109377793 abcnews.go.com Article Entertainment General news Indigenous people Keycat Keytags Race and ethnicity U.S. News visual arts World news -

Mexican film wins top prize at Moscow International Film Festival while major studios boycott Russia

Mexican film wins top prize at Moscow International Film Festival while major studios boycott Russia,A Mexican film has won the top prize at the Moscow International Film Festival which took place as major Western studios boycott the Russian market and as Russia’s war in Ukraine grinds into its third year Tags: 109702159 abcnews.go.com Article Entertainment Fairs and festivals General news Keycat Keytags Movies Russia Ukraine war World news -

Sandra Oh reenacts funny ‘Princess Diaries’ scene for Anne Hathaway

Sandra Oh reenacts funny ‘Princess Diaries’ scene for Anne Hathaway,Sandra Oh re-created a beloved scene from "The Princess Diaries" to announce Anne Hathaway's recent appearance on "The Kelly Clarkson Show." Tags: Movies popculture today TODAY.com -

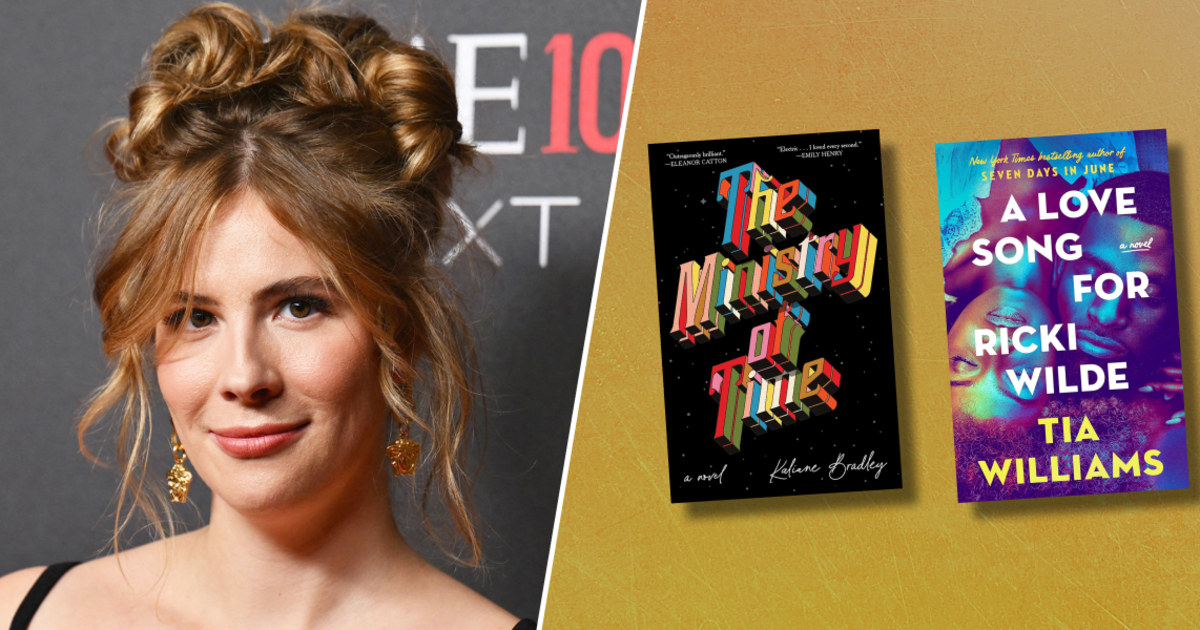

Bestselling author Emily Henry shares her latest book recommendations

Bestselling author Emily Henry shares her latest book recommendations,What is Emily Henry reading right now? She shares book recommendations. Tags: books popculture today TODAY.com -

New York Film Academy’s Miami Campus Updates and Revamps its Labs, Classrooms, and Equipment

New York Film Academy’s Miami Campus Updates and Revamps its Labs, Classrooms, and Equipment,The South Florida campus, known for its proximity to Miami’s downtown, beaches, and film and music venues, gives its location a complete upgrade.... -

Nike reveals Team USA medal ceremony uniforms ahead of 2024 Paris Olympics: EXCLUSIVE

Nike reveals Team USA medal ceremony uniforms ahead of 2024 Paris Olympics: EXCLUSIVE,Nike revealed on the TODAY show the official medal ceremony looks created for Team USA athletes at the 2024 Paris Olympics. Ryan Crouser and Sunny Choi modeled.

Warning: file_get_contents(https://www.scienceradars.com/wp-output-content.php?pg=1&cat=&kw=&lvl=): Failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.1 526 in /home/wwwroot/xuenou.com/wp-content/themes/chromenews/template-parts/content.php on line 169

Warning: file_get_contents(https://www.bayuexiang.com/wp-output-content.php?pg=1&cat=&kw=&lvl=): Failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.1 526 in /home/wwwroot/xuenou.com/wp-content/themes/chromenews/template-parts/content.php on line 173

TrendRadars

The Most Interesting Articles, Mysteries and Discoveries

Prescribing alcohol use disorder medications upon discharge from alcohol-related hospitalizations works